Q&A with Samantha Stanley at Information Futures Lab

The Covid-19 pandemic has made clear how bad information could harm us.

Misinformation, disinformation and malinformation spread rapidly online, undermining public trust in health authorities, fueling conspiracy theories and endangering lives.

It also taught us the importance of experts communicating effectively and having honest conversations with the public about what’s known and what’s not — for example, on how the coronavirus is transmitted and the effectiveness of wearing a facemask.

Researchers at the newly formed Information Futures Lab at the Brown University School of Public Health aim not only to understand the problem of information disorder but to create tools for better public health communication. They help government and community leaders deliver high quality information that people need to make the best decisions for themselves and their families.

We asked Samantha Stanley, associate director of research and program management, about her work at the lab, the state of the media literacy landscape and tips for media literacy educators.

Some of the questions and answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.

Samantha Stanley is associate director of research and program management at Brown University's Information Futures Lab. She is an expert in news media literacy, and her research focuses on the shifting boundaries of journalism and news information and their implications for media education. She received a Master of Journalism and a PhD in Journalism from the University of Hong Kong’s Journalism and Media Studies Centre.

Samantha Stanley is associate director of research and program management at Brown University's Information Futures Lab. She is an expert in news media literacy, and her research focuses on the shifting boundaries of journalism and news information and their implications for media education. She received a Master of Journalism and a PhD in Journalism from the University of Hong Kong’s Journalism and Media Studies Centre.

Tomoya Shimura (interviewer) is one of the few bilingual journalists who write professionally for prominent news outlets both in the U.S. and Japan. He has won awards for his reporting on Southern California’s housing crisis and the influence of super PACs on local elections. His columns analyzing U.S. domestic issues are often ranked among the most read articles in Japan.

Tomoya Shimura (interviewer) is one of the few bilingual journalists who write professionally for prominent news outlets both in the U.S. and Japan. He has won awards for his reporting on Southern California’s housing crisis and the influence of super PACs on local elections. His columns analyzing U.S. domestic issues are often ranked among the most read articles in Japan.

The dangers of using the term “fake news”

— In the U.S., as well as in Japan, we hear the term "fake news" so often now, especially after former President Donald Trump repeatedly used the term to describe whatever news he disliked. But media literacy experts say the term "fake news" is not only unhelpful, but even harmful. Why?

I think the answer partly lies in your question. Certain actors have really co-opted the term, which, in the beginning, didn't have a very clear meaning to audiences to begin with. Is that a news story that's fake? Is it a satirical news story that is meant to look like news? What exactly does that mean?

It was quite an unhelpful term before Trump, but in some ways it was actually helpful that Trump sort of put a little bit more of a definition on "fake news" as a term so that we all kind of have now a common understanding of what it is. Still, I would say as a media literacy educator that the term is not helpful at all.

Everyone is immersed in media right now. Our entire lives are facilitated through smartphones and computers. It's more helpful for people to understand different kinds of content and different motivations. Some content is meant to persuade, some is meant to inform. Sometimes you can't tell the difference.

And I think that's helping people get a stronger sense and a habit of questioning and looking for indicators that help them determine that the difference between helpful and persuasive or misleading content is more important than using the term "fake news."

— Using the term "fake news" oversimplifies something that is very complicated with different motivations and different ways of communication. I believe people should try to identify such differences more carefully rather than just saying everything is fake news when the information appears inaccurate or misleading.

Exactly, or if you just don't agree with it.

Moving beyond categorization

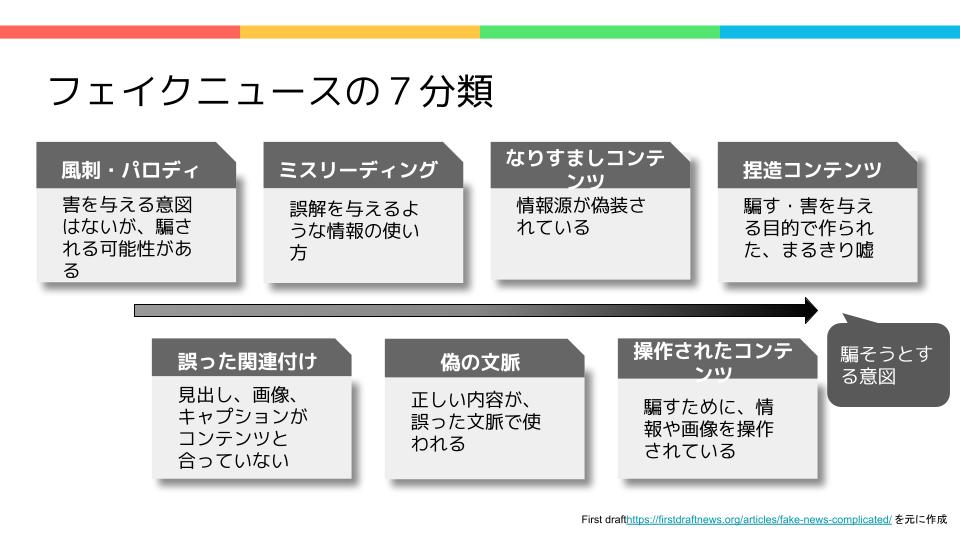

— As a way to avoid using the blanket term “fake news,” your boss, Claire Wardle, who co-founded the Information Futures Lab, broke down fake content into seven categories in her 2017 article based on who is creating the content and why. The seven categories are 1) satire and parody, 2) false connection, 3) misleading content, 4) false context, 5) imposter content, 6) manipulated content and 7) fabricated content.

Japanese translation of '7 types of mis- and disinformation' from First Draft, prepared by the SmartNews Media Research Institute.

However, my understanding is Claire and researchers at Information Futures Lab no longer focus on such categorization of content. Why?

So back in 2017 when Claire published that article, the world was still being introduced to this idea of what this new landscape looks like — how information online can very easily be nefarious or just incorrect in different ways.

Her work at First Draft as an organization really centered around misinformation, disinformation and malinformation, or what she called "information disorder" as sort of like a blanket description of those three types of information issues.

But now the work that we do at the Information Futures Lab at Brown is quite different. It honors and recognizes that history of complicated information that people find online. But what we focus on at Brown, which is a totally different entity than First Draft, is the future of information.

We're no longer trying to alarm the world because I think everyone already knows, and to some extent, some of those phrases are actually becoming weaponized in certain circles. For example, over the last year or so, some people have begun to equate efforts to curb misinformation with censorship.

We certainly acknowledge and recognize that there is problematic content and that misinformation is quite complicated. That's still the case. But right now, we're thinking more about the fuzziness around misinformation and how well-meaning people often share inaccurate or information that's not rooted in fact or science with the best of intentions.

They believe this because their social group or their community or their upbringing or their religious background lays a foundation for them to believe in a pseudoscience, for example, and they really believe it's important for them to share the information with others, or otherwise they could lose their life.

How do you put that into one of those seven buckets? We want to acknowledge that it's even more complicated than the seven different types of misinformation.

— Tell us more about “the future of information.”

Claire and First Draft did the work of shining the spotlight on the issue of information disorder. Now we are asking, "How can we work to strengthen the quality, amount and access to information that people need in order to make good decisions?"

Our work at the lab really focuses on understanding communities as a space where people learn and seek out information to make decisions that are best for themselves, for their family and for their community and society. We're really trying to understand, "How is information shared and accessed in online and offline communities?"

— It sounds to me like the lab has shifted the focus from what the receivers of information should do to what the purveyors of information should do to ensure people have access to reliable and usable information.

What we're trying to do is to focus on solutions. And that's not counter to media literacy. I very much see media literacy as one of those solutions. For example, a media savvy consumer would know that press release content is meant to serve certain audiences and is a product of a public relations component of an organization.

I do still see value in helping those of us seeking information to be better informed about how to do that and what kinds of content they're likely to encounter. So media literacy is naturally part of the solution or one solution to information issues or a lack of an ability to find information for various reasons. Some of those reasons are structural, like, some people don't have high speed internet or are limited to smartphones.

— Is it still useful for people to categorize different types of fake content?

It could be. It never hurts to think more critically about information, and there are a number of different frameworks available to do that. And the seven types of misinformation is one such framework. All of these different tools are helpful for helping people understand the different types of content and motivation and where they might encounter them. I would just say I wouldn't limit anyone to just one framework over another.

Investigating the community information needs

— Tell us about the research you and your team have done at the lab?

Right now we're really focused on understanding community information needs.

Specifically the investigations that we just finished are around three topics. One is reproductive issues, more specifically, abortion and pregnancy, mental health and youth, and then climate and health. We are in a school of public health, so we do focus on health issues.

We look at information related to those three topics — how are people looking for them, what is the quality of information they find when they get there, and then what are some recommendations, like specific SEO strategies to help user-generated questions populate more sought-after answers or ways to present information in a more engaging way via social media, for those in the field to help improve access to the information that's being sought.

— Could you give us some examples?

For example, we did an investigation into what people might find if they are in Rhode Island and looked for resources about mental health for young people. Our team looked into community groups online. We looked at the questions that people ask on Google.

We scraped all of those questions to get an understanding of the kinds of questions people are looking for. What we found is that oftentimes people are expressing frustration over not being able to find resources from local healthcare professionals. That information isn't being delivered to them where they're looking for it.

I don't know if it's easy, but it's fixable. And it's not even a product of any sort of malintent. Perhaps, a local government or a local service provider or a nonprofit group is very strapped for resources. Our intention is to expose some of those gaps.

— How about abortion and pregnancy?

We did an investigation on what it looks like if you're looking for pregnancy resources in Rhode Island. One interesting thing we found is that the top seven or eight resources that are produced if you Google the word "pregnancy" in Rhode Island are crisis pregnancy centers, or CPCs. They're not certified as clinics or as public health providers, but they do provide a lot of information and resources when it comes to pregnancy and pregnancy-related issues.

The caveat is they tend to be quite anti-abortion, and not only do they not give information about abortion as an option, but others actually dissuade or share information that is misleading about abortion processes and the health repercussions.

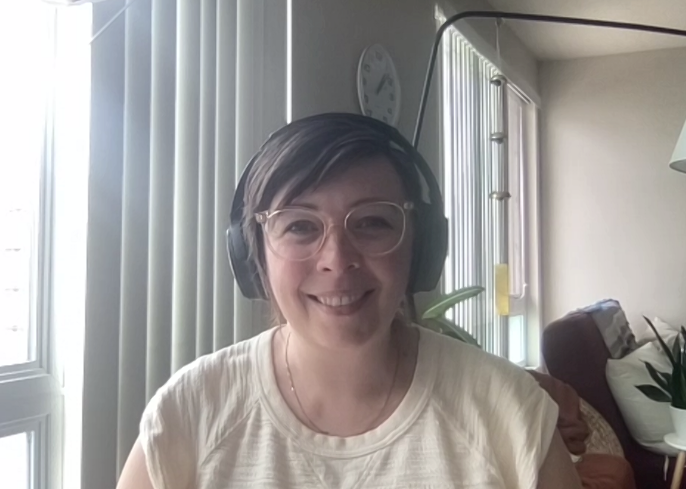

Samantha Stanley talks to the SmartNews Media Research Institute via Zoom.

So if you're a pregnant person in Rhode Island looking for information and you don't think to keep clicking until you find another resource with a broader set of information, that's a limiting factor to your knowledge base as you go into a very significant decision.

We're not taking a stance on whether or not abortion is the right way to go for certain people, but we do think it's fair to have all of the information readily available without having to dig for it.

We also found press releases are often at the top of search results in particular searches we did around this topic in Rhode Island. Press releases from government officials tend to have accurate information, but it might not be written in the best way for an audience who's seeking information about "What do I do right now?"

Sharing information online

— Let’s talk about media literacy. Tell us about your research interest within that field.

My interest is in ensuring that people understand the social, economic, and political landscapes of journalism and the news business so that, as they navigate a growing amount of content, they can better contextualize the information in order to make the best decision for themselves.

For example, a foundational lesson in news literacy is about how news stories are chosen to be published by journalists and editors. As a news consumer, this is an important aspect of understanding who is shaping the stories you are learning from, and why. It also helps you understand the need to consult multiple sources of information to gain a complete picture of a story. But a more modern spin on this is the use of behavioral data to make editorial decisions. Each time you open a news app like Apple News, The New York Times, or your local paper’s app, what you click on, how long you read it, and what you click on next is tracked. Those data points inform how stories are prioritized in the newsroom and the next time you open the app. This is a business practice of the news organization that impacts how consumers access information, and one that consumers should be aware of so they exercise more control over their information diet.

I've always felt strongly that quality journalism is a cornerstone to social welfare. I went to journalism school, so I'm trained to be a journalist. I very quickly understood that while I'm very interested in journalism and its quality and its characteristics, there's no way I want to be a journalist. It takes an incredible amount of tenacity, integrity, and passion to do this work in an industry with shrinking resources. It's just too difficult in today's environment. So hats off to you.

— Let's get into the specifics of what people can do when they encounter fake content. A lot of the dissemination of misinformation and disinformation occurs on social media like Twitter and Instagram. When you encounter information you want to share but not sure if it's accurate, what should you do?

What a sad reality it would be if we had access to social media and weren't able to be social on it. I definitely don't discourage sharing information, but I would say just to take a pause. Over the last several years, there have been a lot of different recommendations to this end where people say, "Just stop and think."

If it seems fishy, it probably is. Or if your spidey senses go off, there's something to investigate. A lot of very complex information is difficult to research on your own. We need to be more thoughtful when we're looking at a set of statistics or some research outcomes in a field we're not particularly familiar with. In those moments, just recognize and be upfront with yourself about the knowledge that you have and the knowledge that you know you don't have and just be willing to be curious and seek out other validation of this information before you share it, and think about who you're sharing it to and why.

— Are there types of information we should be extra careful about?

I'll say coming from a school of public health, there's a lot of information about health research that I think is very important to consider in the world of news literacy.

We teach a lesson around some basic statistics that audiences should understand in order to do a very basic test of whether or not the research that a reporter has reported on is valid. If you see a bunch of numbers, think about a couple of different things.

One, put that number in context of the total population and think about whether or not that number you're seeing is likely to be representative of the population that it's claiming to be. So, for example, yesterday I was scrolling through Apple News and I saw a headline from CNN that read, “Long-term use of certain reflux medications is associated with a higher risk of dementia, study suggests.” My thought process goes something like this: Who are the participants of the study? Are there enough participants in the study to generalize the results to the population studied? Will the article explain this or will I need to verify by going directly to the research?

Those questions are a bit complicated, and there's a lot of statistical calculations that go into answering them, but there are online calculators that can help. And the average person doesn’t necessarily have access to academic research publications. So, I don't expect everyone to use this specific line of questioning all the time, but there are some simple, basic levels of research knowledge that people could have that would help.

The most important thing is just developing the habit of becoming discerning, to think critically about who is creating this content and for what purpose. If you can master those two questions, you'd be doing yourself and others (since your knowledge impacts your actions and your actions impact others) a really big favor.

Racial issues don’t cross borders

— How careful should we be in sharing parody and satirical posts on social media? I believe that could be a tough decision because intent is good sometimes, but not everyone can tell it's humor.

Think about who you're sharing it to and in what context. If you're retweeting something, for example, your tweets have public access, and so anybody can follow what you're tweeting and see it and misinterpret it. In that context, I might put a very clear disclaimer. Some sort of label – a graphic of an “X” or a disclaimer in all caps – might be helpful. Same as fact checkers do.

On the flip side, if you are sharing this within a Facebook group of people you already know, and who would understand this type of content and will immediately recognize it for what it is, I don't think there's any harm in that and no need to label it.

I think it just depends. We all have to think about the audience that's likely to see our content.

— I think we should be especially careful about parody and satire when it has racial connotations. That's one area I could see potential harm.

Yes, and something that I learned that was really interesting teaching in Hong Kong is that the understanding of racial issues does not cross borders.

Here in the U.S., race is a very important issue, and it's very specific to the context and history of the U.S. and to the social fabric of what we're living in. While people from outside the U.S. see that and they understand it, it doesn't necessarily translate.

I was teaching an ethics class in Hong Kong and I used an example of a political cartoon in a newspaper from Australia that had exaggerated some of the features of Serena Williams after she had made a fuss over a match against Naomi Osaka.

It was interesting because a lot of the students didn't like that I was approaching this as an American with a very specific understanding of what that kind of characterization does and means in that context and some of my students didn't understand.

That's just another really important aspect — that my social construction of reality and my own experience inform how I understand these things, and that doesn't necessarily cross borders, but content does.

— That's a very good point because I run into the same issue when I tweet in English and Japanese. I often interact with both groups and they have very different attitudes about, let's say, race. What should we do about such cultural differences? Information you post on social media goes beyond geographical borders.

I think in an ideal world, we would all have the opportunity to learn more about different cultures and about cultural understanding and history and historical racism in different countries. Asia also has very strong roots in race and ethnicity issues that an American might not understand in detail without having been there.

If we can learn from each other about these different contexts, that's the best case scenario. The worst case scenario, or the minimum that we can do is just be thoughtful and conscientious and think critically about the content that we're sharing.

If you're about to tweet a characterization of a person, think about what features have been exaggerated. And try to take yourself out of your own worldview for a second before you share.

The changing media landscape

— With the advent of AI, photoshopping and other technologies, it's becoming much more difficult to discern inaccurate information. For example, researchers at the University of Washington used an AI technology to produce a photorealistic Barack Obama making a speech. What can we do to identify such content that looks and sounds so real?

They are difficult to discern, especially for older people. There was a study recently around young people and old people and their ability to spot visual fakes. Young people are more quicker and more accurate. I'm going to be honest with you, I'm not totally sure what to do about increasingly sophisticated deep fakes.

I know that right now, if you really look closely at deep fake images, there's usually a tell, maybe like an ear is not quite right or there's like a glitch or something. If you really scrutinize a photo, more often than not you can find something that's a little bit weird looking that might tip your hand.

There's a program that generates a deep fake and a real photo side by side. It's kind of like a game where it produces these images and you try to click on which one is the fake. Practicing with things like that is helpful because you start to see like, "Oh yeah, I didn't see that. That tree is not really complete."

But I don't know what the answer is. I do think part of it should be that we should be having discussions with students in computer science and emerging technologies around the ethics of this. Just because we can, does that mean that we should?

— We are also seeing new technologies such as ChatGPT come to life. Tell us about the changes in media literacy that we've seen recently.

Media literacy is such an interesting space. In some ways, it seems as though it has changed quite a bit, and in other ways, not at all.

There are a number of different philosophies on media literacy, and it can be quite contentious within. There are some conflicting ideas about what's important and what's responsible and what's ethical, and that hasn't changed, unfortunately.

Obviously, media literacy educators are learning more about emerging technologies, and they are utilizing those technologies not only in their own practice, but also helping students understand technology and its uses. What I would love to see more of in media literacy is a critical look at those technologies and what they mean for society.

— Could you elaborate on that last part?

There are a lot of resources that help media literacy educators become aware of emerging technologies and to teach about them in the classroom. They are provided most often for free to very busy educators with limited resources, and they're presented as out-of-the-box, ready-to-go resources that they can implement in the classroom, which is very helpful for educators.

However, a lot of those resources are created by media technology companies themselves, which can be quite a conflict of interest.

One thing that I would love to see is more resources to help media literacy educators evaluate the quality of those products so that they can use them as they feel is appropriate for their classroom, but also supplement with some more critical discussion of chat bots, for example.

I'm part of a fellowship right now where I'm working with a colleague from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and we're trying to create a framework or a decision-making tool or an evaluation tool to help media educators contextualize and evaluate the quality of these types of products.

What educators and journalists can do

— Speaking of educators, what can teachers who are tasked with educating young people who are exposed to overload of information on social media do?

There are so many resources available. Going back to the struggle within the media literacy community, there's a lot of different philosophies when it comes to how to teach, who to teach and what to teach. I think exploring those different communities is a great first step.

There's a national organization in the United States called NAMLE, the National Association for Media Literacy Education. That's a great first step in understanding who is working on media literacy. Just starting to understand the communities and resources available, getting your feet wet and advocating within your school system that this works are important.

—What can the media and journalists do to help improve media literacy in their countries?

My understanding of the media landscape and journalism in Japan is that they are quite different from the U.S. We all need to recognize that there's no blanket solution, that journalism does look different in different countries, even in democratized countries, and there's no one formula that fits all for media literacy education.

One thing I really value about Dr. Kajimoto's (Masato Kajimoto at the Journalism and Media Studies Centre of The University of Hong Kong) philosophy is that the work that he does in Asia is not prescriptive. He helps shine light on the areas that need to be discussed as part of news literacy and shares pedagogy and teaching approaches.

He really emphasizes that it is very important for this content to be localized to the political, economic and media landscape that the educator is working in. One big thing that media organizations could do, and I think journalists are getting better at doing this, is just reflecting on the impact that they're making.

A lot of journalists are, understandably so, in the media environment that we live in. It's very click driven, it's very data driven. Newsrooms have to make a profit, and that's all part of a bigger system that journalists have to operate within.

Tomoya Shimura, right, interviews Samantha Stanley about media literacy via Zoom.

—That’s so true. And journalism is evolving.

Some of the changes in the ways that journalism is produced and displayed can be quite confusing to audiences. A striking example is the prevalence of native advertising as a revenue source for news publications. Native ads are constructed to look and feel like news content that the organization publishes, but the content is paid for by an advertiser. This advertising product is designed to be stealthy by borrowing the characteristics of the trusted news publication to influence readers without them necessarily knowing they are reading or viewing an ad. Most major news publishers have resources in-house to produce these kinds of ads for clients because, who’s better to design a “Timesean” native ad than the folks working at the New York Times? The use of this ad format could have real implications for how the public understands BP’s impact on climate change, or Wells Fargo’s influence in microlending. The last thing I’ll say about native ads is that as more journalists are losing their jobs in the newsroom, opportunities to redirect those journalistic skill sets to native advertising are plentiful. So just thinking a little bit more about these kinds of business implications and trying to balance some of those changes with the responsibility to the public would be great.

And work with media literacy educators. I know a lot of them do. The News Literacy Project is a great example of an organization that works directly with journalists. Also, because jobs in journalism are becoming fewer and fewer, a lot of journalists are becoming educators. And becoming a thoughtful educator is really important. Having the skills to do something and imparting those skills is one thing, but true education also includes reflection and a knowledge base that goes beyond skill sets and should include societal impact.