More knowledge isn’t always better: How media literacy education protects democracy~Interview with Dr. Joseph Kahne

There’s no doubt that the political division in the United States is impacting our discussions on major issues we face, such as how to respond to economic disparities and climate change.

Because the internet allows anyone to disseminate information, it’s becoming ever more difficult to discern more credible from less credible information. Some may think we should equip ourselves with more knowledge to help us navigate through this age of misinformation. But a study suggests that people with political knowledge aren’t necessarily better at discerning accurate information. In some cases, they perform worse than people with little political knowledge.

We talked to UC Riverside Professor Joseph Kahne, who co-authored the study, and asked him about key findings from his research and the importance of media literacy education.– Tomoya Shimura

Joseph Kahne is the Ted and Jo Dutton Presidential Professor for Education Policy and Politics and Co-Director of the Civic Engagement Research Group at the University of California, Riverside. Professor Kahne's research focuses on the influence of school practices and digital media on youth civic and political development.

Joseph Kahne is the Ted and Jo Dutton Presidential Professor for Education Policy and Politics and Co-Director of the Civic Engagement Research Group at the University of California, Riverside. Professor Kahne's research focuses on the influence of school practices and digital media on youth civic and political development.

Tomoya Shimura is one of the few bilingual journalists who write professionally for prominent news outlets both in the U.S. and Japan. He has won awards for his reporting on Southern California’s housing crisis and the influence of super PACs on local elections. His columns analyzing U.S. domestic issues are often ranked among the most read articles in Japan.

Tomoya Shimura is one of the few bilingual journalists who write professionally for prominent news outlets both in the U.S. and Japan. He has won awards for his reporting on Southern California’s housing crisis and the influence of super PACs on local elections. His columns analyzing U.S. domestic issues are often ranked among the most read articles in Japan.

Political beliefs change the judgment of "whether it is true or not"

――Your 2017 article, ‘Educating for Democracy in a Partisan Age: Confronting the Challenges of Motivated Reasoning and Misinformation,’ investigated how young people judged the accuracy of truth claims tied to controversial issues. Would you please explain how you conducted this study?

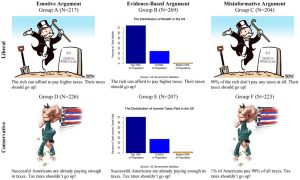

We had a survey that we were going to give to young people ages 15 to 27. And on that survey we included what might be thought of as a Facebook post or an Instagram post, basically a politically oriented cartoon, or it could look like a graph or a graphic, but some kind of political post.

And we asked respondents to tell us if they thought those posts were accurate. Some of the posts that people were randomly exposed to were accurate, and some of the posts they were exposed to weren't accurate. We also asked them in a separate part of the survey about some of their political beliefs, and we also had a measure of their political knowledge. And we also had a measure of whether they had received any media literacy learning opportunities.

This allowed us to test whether they could correctly assess the accuracy of the post and whether those other factors — political knowledge, media literacy learning opportunities, or their partisan beliefs — help to predict whether or not they correctly identified the post as accurate or inaccurate.

――What did you find out?

Posts used in the survey

What we found out, most importantly, is that the best predictor of whether or not a person thought a post was accurate or inaccurate was whether or not the political perspective implied by the post aligned with what they believed politically.

The posts were about taxes, and if they believed that taxes should go up and if the post implied that taxes should go up, they were very likely to say it was accurate. And they said this even if the reasoning behind the post and the information included in the post was wildly inaccurate. And the opposite was true as well. If their political beliefs did not align with the post, they were likely to say the post was inaccurate, whether or not the post was actually accurate.

Now, it also did matter whether the post was accurate to some degree. People were more likely to say a post was accurate if it actually was accurate or used accurate information. But the relationship between the actual accuracy of the post and whether they said it was accurate was much weaker than the relationship between whether or not their political perspective aligned with the post and what the post was promoting.

Media literacy helps us discern information

――Here's what we found particularly interesting. This is a passage from your article. "In particular, we found that the influence of directional motivation was greatest for those with the most political knowledge and that, counter to expectations, those with high levels of political knowledge were no more likely than others to correctly identify inaccurate truth claims." So in other words, those with political knowledge have difficulty escaping their biases, even if they are presented with evidence. Why?

So judgements about whether something is accurate or not are based on a person's reasoning, and their reasoning can be motivated by different factors. Some people are motivated by a desire to be accurate.

Some people are going to be motivated by what they already believe is true or already believe is desirable with respect to their political beliefs. And we call that directional motivation because rather than their judgment of the post being based on the quality of the argument, their judgment of the quality of the argument is based on whether or not they liked the conclusion that the argument came to. And so what we found was that more often than not, rather than letting the quality of the argument influence their beliefs, their prior beliefs influenced how they judged the quality of the argument.

And then what we found when we brought in this question of knowledge was you would think that people who had more political knowledge would use that knowledge to judge whether the argument was correct or not, but that's only going to be true if people are motivated by what we call accuracy motivation, by a desire to be accurate.

But if the big thing motivating them is directional motivation, — their desire to get to the conclusion that they already believe is true, to promote the policy they already like — then those people who are knowledgeable use that knowledge to justify what they already believe. I think we see that happening in the political system a lot.

Professor Kahne giving an online interview

So if that's true, and we found it to be true, and that being knowledgeable isn't, doesn't solve that problem, then that's a really important thing for educators to think about, because it means simply educating people about political issues is not going to necessarily lead them to make well reasoned judgements about the arguments that they see. Rather, it's going to lead them to use their intelligence to come to a conclusion that is consistent with what they already believed.

And we see this happening in our political lives as well, which is why hyper partisanship can be so destructive to the value of political discourse. Because the premise of political discourse or the hope is that as people engage with one another and discuss issues, they will learn, and they may shift their opinion to believe something different based on well reasoned arguments. But if they're only using arguments to justify what they already believe, then the whole exercise of debate doesn't have a big benefit.

So then what should educators do?

Our study was designed to try and respond to this question. We found that if people had training in media literacy, that did increase the likelihood that they would make judgments about these posts that were closer to whether the posts were actually accurate or inaccurate. What that's about is the fact that the media literacy education really focused students on the importance of judging the accuracy of information. So in essence, that educational effort was designed to promote what we call accuracy motivation rather than designed to promote directional motivation.

――Just want to make sure I understood it correctly. Let's say, for example, if a student who took the survey was politically conservative with very high political knowledge, they are more likely to say that liberal posts are inaccurate than a less knowledgeable conservative person?

Yes. Now there've been multiple studies of this phenomenon. There are some times when people find that political knowledge doesn't help. And there's sometimes when people find that it actually hurts. And you can imagine, it depends on the person, but the basic finding, which is in our study and in many others, is that knowledge is more likely to be used to help people to rationalize an inaccurate statement or critique an accurate statement that argues for the other side, than it is used to make a reasoned assessment of the argument.

And this is true for liberals and conservatives. So if liberals who are very knowledgeable are presented with a conservative argument, they often use that knowledge to undercut and to criticize the accuracy of the thing they were just shown. But if they're shown a liberal argument, one that aligns with their beliefs, they don't use their knowledge to undercut that argument. And similarly with conservatives. If conservatives that are knowledgeable are shown a liberal argument, they use their knowledge to undercut it. But if they're shown an argument that aligns with their beliefs, they don't.

When you're thinking about people who aren't that knowledgeable, part of what is going on is that those people aren't necessarily aware of whether this argument supports their beliefs or doesn't. Because often, for example, political ads use sarcasm. If you don't know much about the topic, it's very hard to interpret what's even being argued. And if you're not that knowledgeable about politics, you may not have a preformed opinion on what should happen with a given political issue. You're less likely to make judgements based on your prior political beliefs, because you may in fact not have very strongly formed prior political beliefs.

What it takes to protect democracy

――So it sounds like people with more political knowledge have more materials that lead them to making wrong judgments.

Yes. They don't want to question what they already believe. That's a human quality. If you already have a strong belief, why would you choose to question it? Suppose you're a person who has believed that conservatives are good and liberals are bad. Growing up, you were in a family where everybody always said, ‘Conservatives were good and liberals were bad.’ And there were lots of examples at the dinner table or wherever used to justify that.

So then you see an argument that might imply that actually conservatives are bad and liberals are good. You've had all this prior experience and knowledge that led you to the other conclusion. So you're, within your mind, ‘That can't be true.’ Now you're going to use your intelligence to disprove it so that you don't have to call into question this thing you've believed for your whole life.

――I can think of so many instances of that happening to myself.

It's a very natural occurrence. And it can play out in different ways. This isn't in our study, but there've been studies that give people an editorial that argues for a given point, but it's not a topic that most people know anything about. And so in this made up editorial, they say the Republican legislator said X and they ask people to judge the quality of the argument.

When they give it to someone who is a Republican, they judge the quality of that argument higher than when they give it to someone who is a Democrat. They then give the exact same editorial, but they change it to a Democrat. And all of a sudden, people who are registered Democrats are rating the article higher than people who are registered Republican.

photo credit: UC Riverside School of Education

So what we really have to do if we want to have high quality discussions, and if we want to have people learn to wrestle with issues is they need to become aware of this process, and they need to be oriented towards being careful and towards accuracy.

And there are experiments to show this, too. If you talk with people about the importance of being accurate and being careful, people become more accurate and careful. Even if you just tell people, "I want you to make a judgment of this article and then I want you to explain that judgment to these other people who are going to be in the next room." Just asking them to do that makes them more likely to make what are actually accurate judgements than if you don't require that they explain or justify their stance to anyone else.

As educators, that's one of the big takeaways from this. Our media literacy education should really emphasize the importance of accuracy so that people have a taste for accuracy or a commitment to accuracy. And when they see arguments using inaccurate data or logic, even when those arguments support the conclusion they like, they rate the argument as bad. That's so important for a democracy.

One reason it's bad for democracy if people don't do that, is that then they don't correct their beliefs based on evidence. People don't end up having well substantiated beliefs. The second reason it's really bad is that if you look at your political opponents and you know that your political opponents are making arguments that use bad logic, then you are much less likely to believe in democracy. Why should I accept the legitimacy of my political opponents if they are driven by illogical arguments, right?

It's one thing, if we're debating what should happen with tax policy or climate change or whatever, and everybody's using accurate information. I might say, "Well, they have a good reason for their position. It's just not what I believe in." Then I'm more likely to view the democratic process as a legitimate reasonable process. But if I believe that they are driven by complete fallacies, why should I accept the legitimacy of what they do? And why should I accept the legitimacy of democracy?

――What was your reaction when you saw the results of the study? Were you surprised by the results or did they confirm your hypotheses?

That's an interesting question. I would say that while the results were consistent with some of our hypotheses, it was still just surprising to see — especially because I work as an educator. For example, seeing that being politically knowledgeable doesn't help, even though I knew that was a possibility, it still does surprise me when I look at it and I'm like, ‘Oh my god, these people who know a lot more about politics, their judgments are not better.’ In fact, in some cases they're worse."

Continued effort required

――What about media literacy education that allowed young people to overcome their bias in your study?

In the study, what we found was a couple things. One is that when students were taught skills needed to judge the accuracy of what they were being exposed to, they become more likely to correctly judge the accuracy of content. There are some skills that allow you to, for example, fact check. So for example, this isn't part of our study, but we have colleagues who teach a process of civic online reasoning, which teaches people to do lateral reading. If they see a post and they're not sure if it's accurate, they open a new window and they Google things about the organization that posted it. They do an independent web search of the factual claims that are being made. So there are ways, there are skills, there are practices that young people can learn that help them judge the accuracy of content.

But the other key point is that it's not just about whether you can do something, whether you have the skills to do something, it's also whether you have the motivation to do something. And so the other big thing that we found was that when teachers talked with students about how important it was to be accurate and talked to them about the risks of being inaccurate, in a sense when they developed young people's taste for accuracy or commitment to accuracy, that also had a powerful impact on whether or not young people were able to identify inaccurate political posts. Because, as we've said, knowledge on its own won't solve this problem. People, if they don't have a commitment to being accurate, won't use that knowledge. They won't be motivated to draw on their knowledge to be more accurate.

――You noted in the article that one limitation of your data is that you relied on self reports of receiving media literacy learning opportunities and the study lacked details on the media literacy learning opportunities that students received. How much media literacy training do you think is necessary to overcome the biases?

That's a good question. My sense from our study and some other studies is that a few days in a given year will help, if it's well delivered. But I don't know that a few days will help in the long run. We don't know from these studies how long those practices hold up. I would guess — this is really my intuition and we have not studied this — that you would want to address these issues on an ongoing basis throughout a young person's education and that would build up both the capacities and the commitments to be focused on accuracy.

I don't think it takes a month-long process to learn many of these skills, but it does take ongoing opportunities to practice them. And it takes reinforcement, because within the culture, there will be other forces that will push in the other direction. If you're reading news from a highly partisan source, some of those highly partisan sources really push you to embrace weak arguments and they aim to activate your emotions in ways that make you much less interested in accuracy and much more interested in winning. So the idea that you just spend a week on this and you're inoculated for the rest of your life, that's silly.

From the standpoint of research, there's a real value to doing what we would call a field trial through which one could experiment with or test different treatments. Some might be a one day treatment. Some might be a one week treatment. Some might be three one-week treatments. And you see whether that dose or that treatment has a differential effect on how people behave when given these kinds of questions. That would be future work that would be great to do.

Increased risks due to changes in the digital environment

――What motivated you to conduct this study?

My big interest is in civic education. It was becoming very clear that digital media was creating new challenges with respect to misinformation. So I really wanted to understand how that played out and what we might be able to do to confront it.

Let me say something about the digital environment, because I think this is important.

The challenge of directional motivation, of people being motivated to justify something they already believe, that problem has always been with us. At the same time, when most people got their news from what we might call consensus news sources, when news was not highly partisan, at least in as explicit a way as it is today, and when most people saw the same news, rather than some people getting news with one political persuasion only, and other people getting news with another political persuasion only, that made the risk of motivated reasoning less. It made the challenge less because people were getting a consensus story about information.

photo credit: UC Riverside School of Education

Moreover, the editorial teams of those organizations were driven by accuracy to a large degree. They had an ethos of, ‘I don't want to show things to the public that are inaccurate.’ Now that doesn't mean they didn't sometimes have biases. Everybody has biases, but there was a culture among those news organizations that tried to emphasize accuracy. You check your sources. If you make a mistake, you acknowledge it and publish a retraction.

Both the advent of cable news, in the U.S., at least, I don't know the situation in Japan, and the internet, have meant that there are tons of distributors of news and information who aren't committed to accuracy. They're committed to getting people to click on what they post or they're committed to pushing a particular political perspective. And there's no way to police those things. So tons of inaccurate stuff gets shared all the time.

That's different than when most people were watching network news shows or reading major standard newspapers. The environment has gotten a lot more saturated with misinformation. And that makes the challenge of dealing with motivated reasoning even more important, because even if people were subject to motivated reasoning in prior eras, if they were being shown largely accurate information, that helped them lessen the risk. They weren't being exposed to as many falsehoods.

Parents pressure teachers

――Tell us about the significance of media literacy education in this day and age.

In the internet age, we're in an environment with far fewer gatekeepers and we're in an environment in which those gatekeepers have less of a commitment or an incentive to make sure that information that is shared is accurate. Thus, it is even more important that all of us as individuals have both the capacity or the skills necessary to make judgments of accuracy and that we have a commitment or a value system that leads us to want to be accurate. Media literacy education can provide those two things.

――Do you think things are getting better or worse in terms of the state of media literacy in the United States?

I don't have great evidence on that, but I think it's an important question. I would say that we are seeing a modest increase in the degree to which schools are addressing this issue. But I would not say that the modest increase in effort is anywhere near adequate for the size of the problem.

Within the U.S., where schools are increasingly feeling pressure from parents not to talk about political issues or to talk about political issues in a certain way, it becomes even harder for educators to address these issues. Something that very rarely happened in the past, for example, parents complaining about pretty reputable news sources, now commonly happens. A teacher will use a New York Times article in a classroom and a parent will complain to the principal that they shouldn't have used that news article. Often the article is just a basically mainstream representation of the situation.

But often what some of these parents want is for their kids to be exposed to factually inaccurate content. That puts educators in an incredibly difficult situation. It is the job of education to champion accuracy. Educators should be nonpartisan when it comes to political issues, but there's nothing wrong with educators saying that students should use accurate information. So if a person says COVID is a myth or the vaccines don't work, when there's clear factual evidence that they do, an educator can't say, "You're right. People don't know whether vaccines work." They could say, "We don't know whether or not we should require that people get vaccines." That's a debatable question. But often educators are in the position now of being criticized for sharing factually accurate information. That obviously makes the job of education much harder.

Education has a role to play

――What do you think are the solutions to all the things that we've talked about?

Dr. Kahne and Mr. Shimura

Now, ‘solution’ is a high bar. I don't think we're going to solve the problem in the sense that the problem will go away. I don't want to imply that if educators put in a couple more days on this stuff, all of a sudden the problem will disappear, I don't believe that. But I do think education has a role to play and I do think educational institutions can help in meaningful ways. I think expanding media literacy education and emphasizing both capacities for judging the quality of media as well as building kids' commitments to accuracy will help. And I think that when educators are talking with parents, it is important to emphasize that ‘We will inevitably talk about politically charged issues at times in school, but we do that because it's vital that we prepare young people for life in a democracy where they're going to have to learn how to make reasoned judgements.’

I think having parents stand up for the importance of those ideals will also help. Often the most extreme and often partisan people are the ones who show up at school board meetings to push their agendas. They have every right to show up, but it would help if other people showed up as well to emphasize the importance of helping students learn to judge the credibility of online content and to draw on accurate content when reaching their own decisions about controversial topics.

――What's next for you?

We're always working on a number of projects. One big question is whether specific efforts can improve young people's media literacies in the ways we've been talking about.

Also, I'm very interested in gaining a better sense of our current politics of education. It feels important to learn about ways that school districts and educational leaders can deal with some of the very difficult pressures they're facing right now. Thinking about ‘How do we help schools really focus on the democratic aims of education?’ is something I'm very excited about. Thinking about ‘What can educational leaders do?’ ‘What can policies do, as well as what shouldn't policies do?’ so schools can do a better job preparing young people for democratic life.

――Politics at the school district level, that's such a hot topic right now. I think it would get a lot of traction because I see school board meetings are becoming a hotbed of these grassroots political movements. So I'd be excited to read your findings.

Click here to read Professor Kahne’s article on what teachers can do to support students in the misinformation age.